The high-profile challenges of PG&E have led some to believe that public ownership of utilities will always produce the best results and lower costs. The truth is far more complex.

A good illustration of this is the recent costly and failed public takeover of a privately owned water system in the town of Apple Valley, a rural community in San Bernardino County. The outcome has implications for all of California and should encourage policymakers to focus on how well our utilities are managed and regulated, and to ensure they are providing safe, cost-effective services to consumers, rather than whether they are simply public or private.

Apple Valley gets its water from Liberty Utilities, an investor-owned private utility — also known as a “regulated utility,” as its rates are regulated by the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC). Neighboring towns are served by municipal utilities, and Apple Valley argued that taking over the system themselves would lead to lower rates for residents. Liberty ultimately demonstrated that the town’s claims were false, and that their private water utility rates were not higher. The case further revealed that compared to their neighboring municipal utilities, Liberty also did a better job of protecting and investing in safe, reliable water infrastructure.

The City of Apple Valley’s expert witness testified that Liberty’s rates were the highest of 31 “similar” water systems. However, those claims failed to account for connection fees, which are charged when a new user is connected. Liberty does not charge connection fees to new customers at all, while other municipal agencies do. That’s an additional cost to consumers not captured in rates.

In addition, the City of Apple Valley did not look at Liberty’s low-income rate assistance program. This program helps low-income customers pay significantly less than CPUC-approved water rates. Many public agencies in the area do not have such a program.

Most importantly, the evidence reveals that rates charged by other agencies rarely reflected the true cost of service. This is because municipal systems regularly delay needed maintenance, resulting in the appearance of their agencies coming in under budget — at the expense of crucial investments in infrastructure. For example, one neighboring city was found to be on a 955-year replacement cycle for their infrastructure, meaning it would take nearly 1,000 years for the entire system to be 100% upgraded.In contrast, Liberty replaces 1% of its system each a year, a ten-fold superior metric. Liberty also enjoys exemplary quality standards, whereas surrounding systems were found to have a number of health and safety violations.

As logical as it may seem to believe that local control is in the interest of the customers, the truth is that surrounding public water agencies engaged in unwise accounting and fiscal practices with limited transparency. The rigorous and fully transparent regulations set forth by the CPUC actually provide superior accountability for residents of rural areas served by private water utilities.

In the end, the judge dismissed much of the evidence brought forward by the city, finding Liberty’s careful research decisive. In this case, the private utility proved that it was delivering higher quality water services with greater value than surrounding municipal utilities. Along the way, a significant amount of Apple Valley taxpayer dollars were spent on lawyers instead of local parks, libraries and public safety.

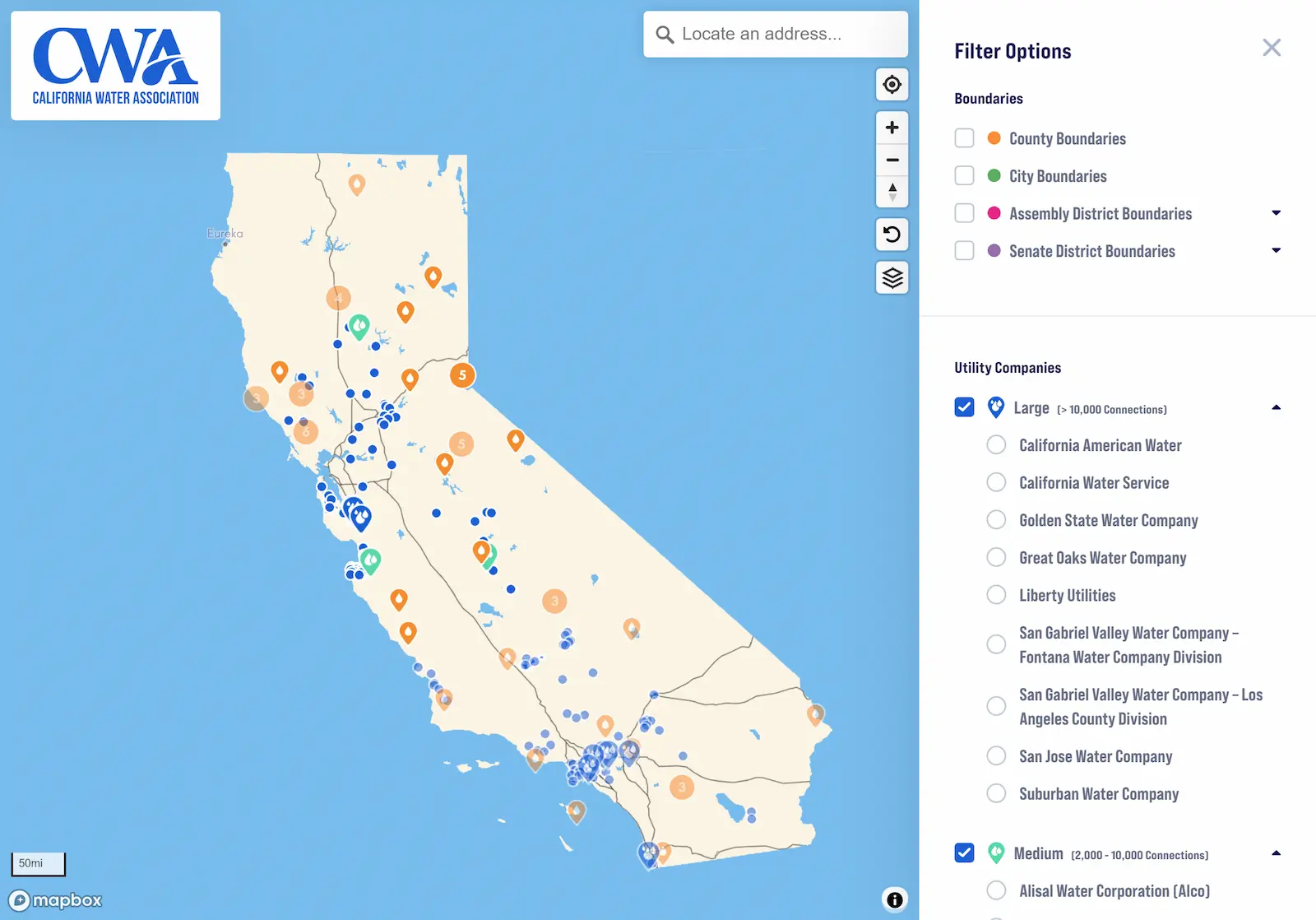

Policymakers at the state and local level would be smart to look at this case and recognize that regulated water works when water professionals are left to do what they know best — deliver clean and safe water to Californians — without the fear of politicized takeover attempts. Private water utilities have played a role in constructing and maintaining water systems in California since the founding of the state, currently serve about 15% of Californians, and have been regulated by the CPUC for over 100 years. Apple Valley is the latest case that proves regulated water works.